Design

The future of airport design with Curtis Fentress

Every year, global architecture firm Fentress Architects launches a student competition challenging participants to envision and design the airport of the future. Adele Berti speaks to the competition’s founder Curtis Fentress about the winning projects and how they incorporated new technologies, climate change and other key trends.

The Fentress Global Challenge is an annual student competition that invites participants from all over the world to envision and design the airport of the future. Organised by Fentress Architects — the Colorado-based firm behind landmark airports such as Denver, Incheon and Seattle-Tacoma — the project has been running since 2011.

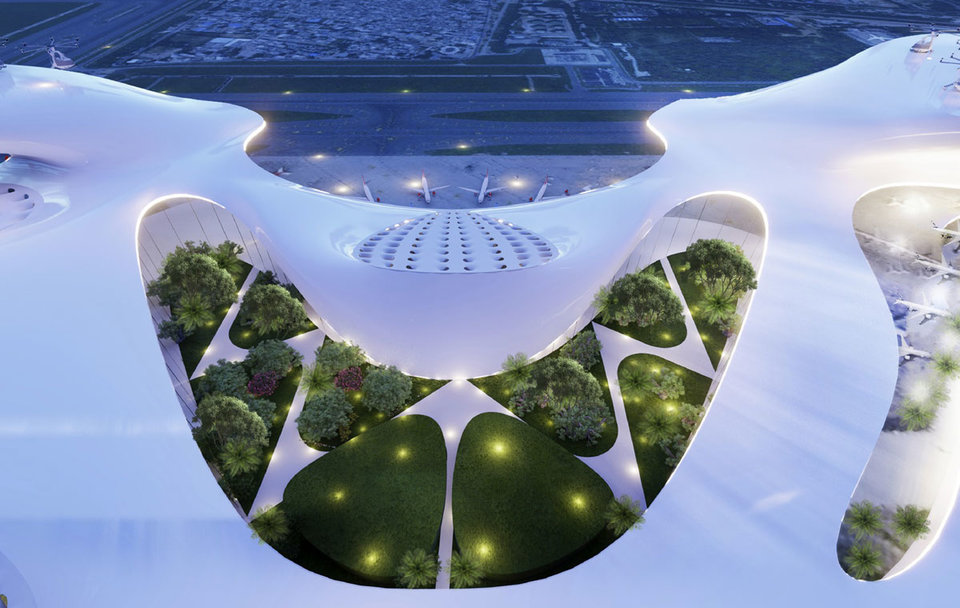

This year’s brief was to design what airports could look like in 2100, keeping in mind key trends such as biometrics, touchless technologies and climate change. As revealed in October, these were best represented in ‘Green Gateway’, the winning design submitted by students of the Southern California Institute of Architecture. The group re-imagined New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport as a multimodal hub with sustainability at its core, made of a central terminal and six towers located around the city.

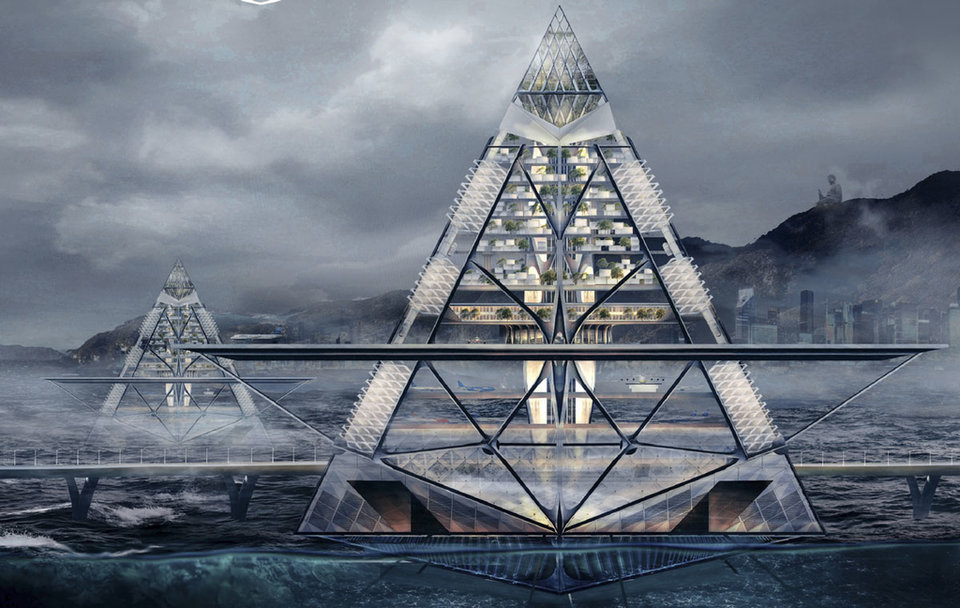

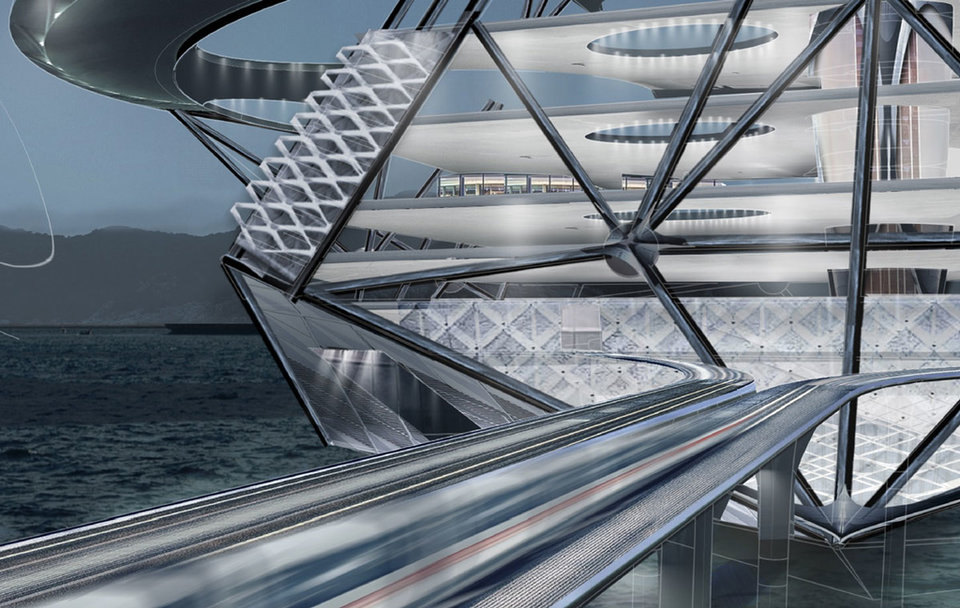

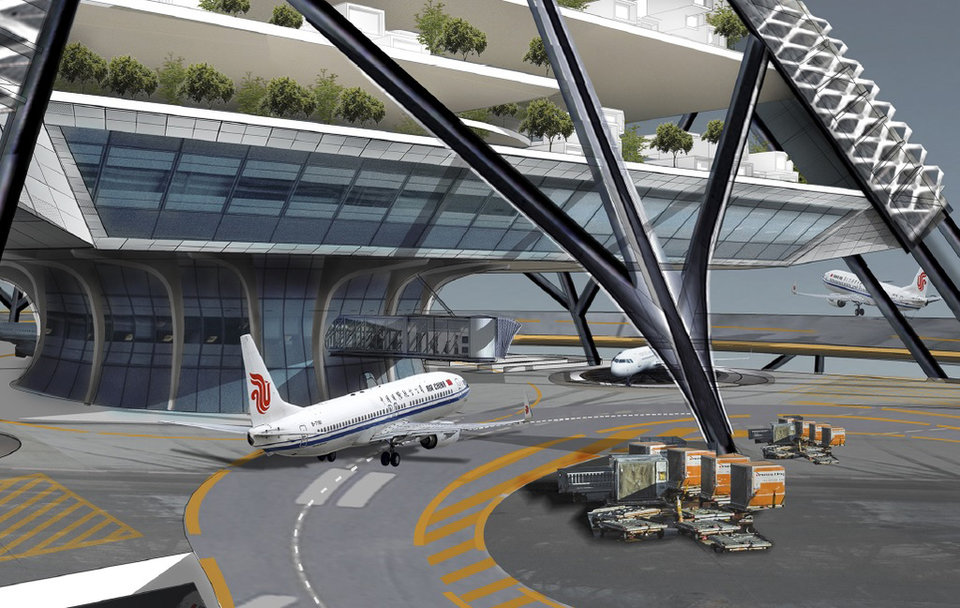

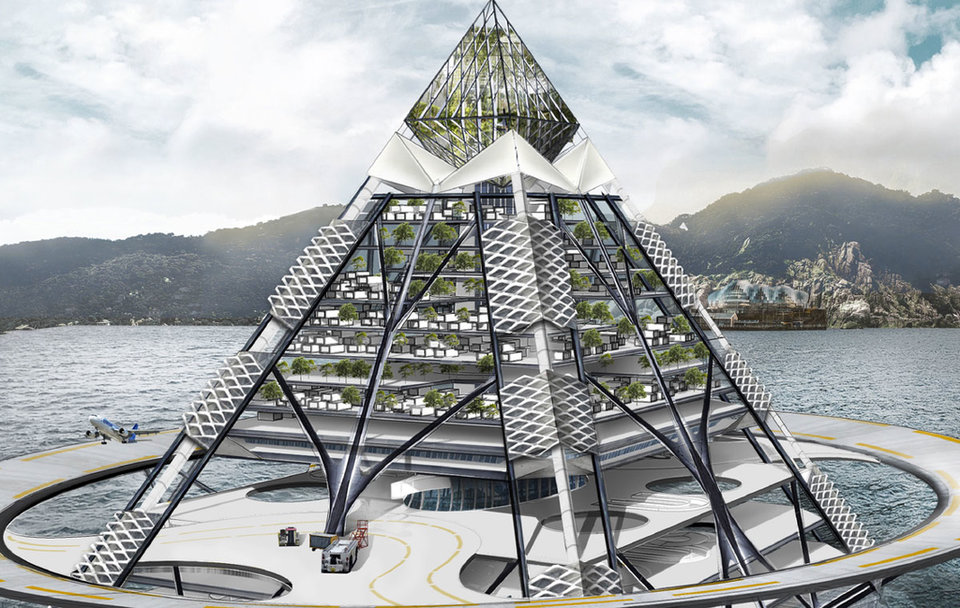

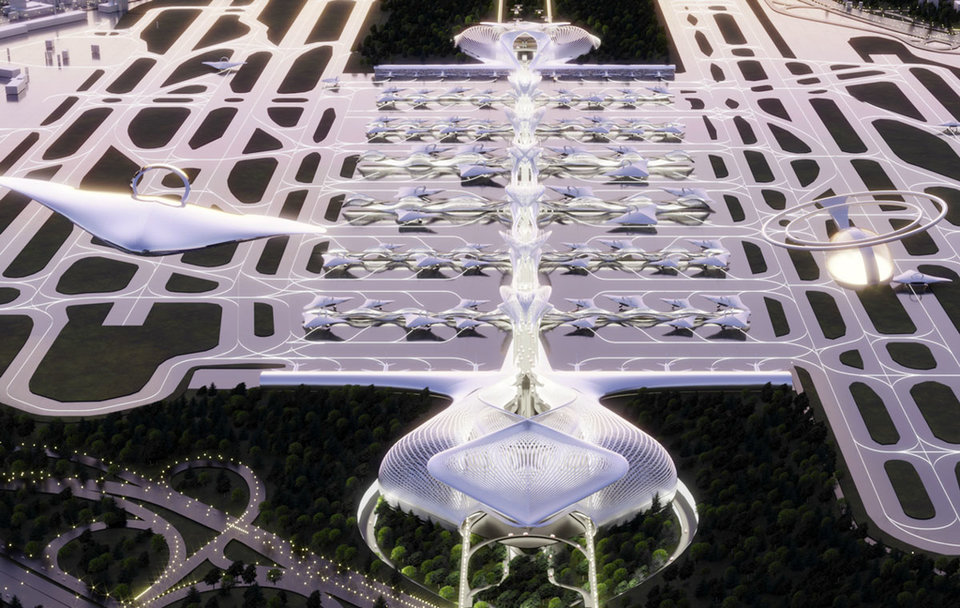

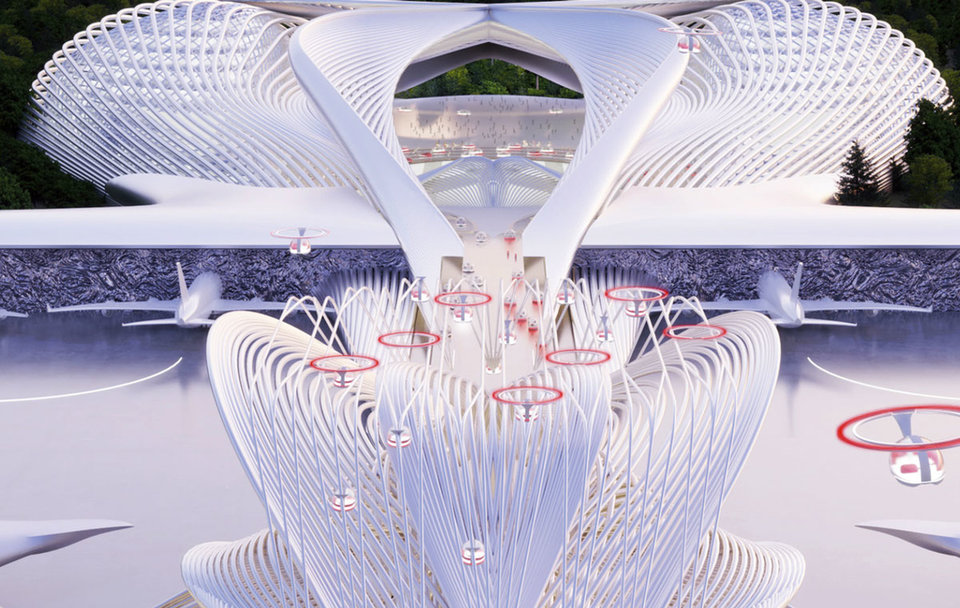

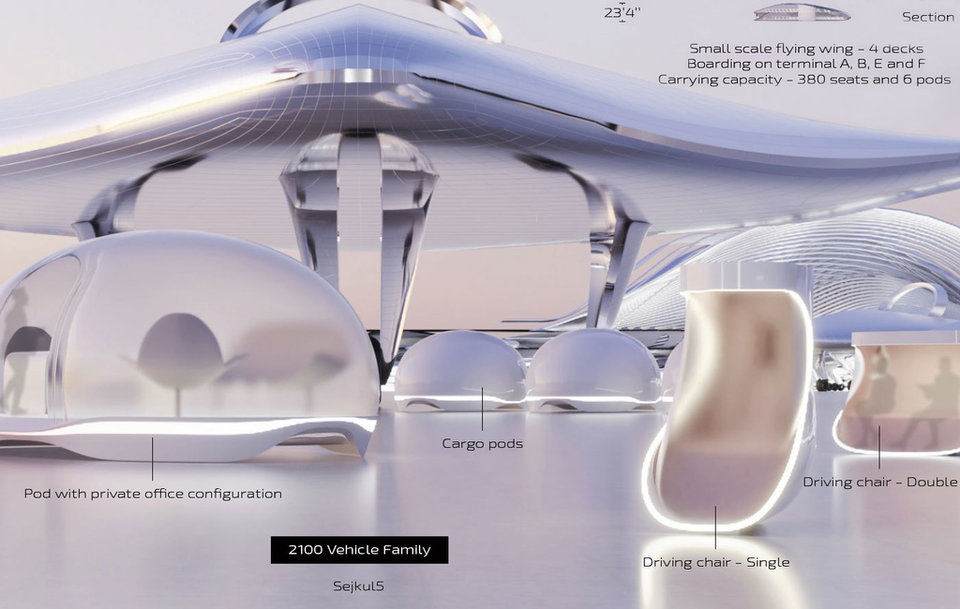

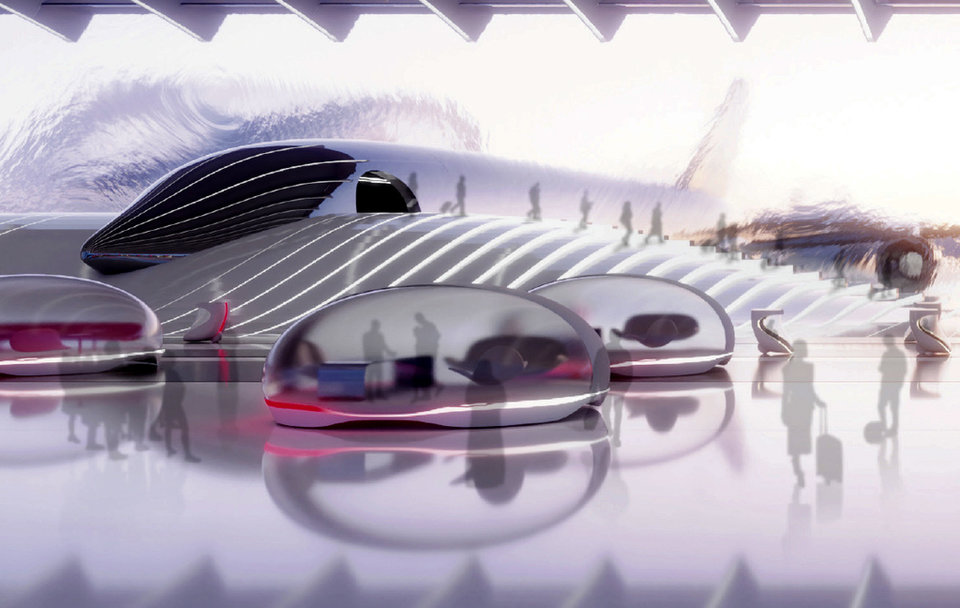

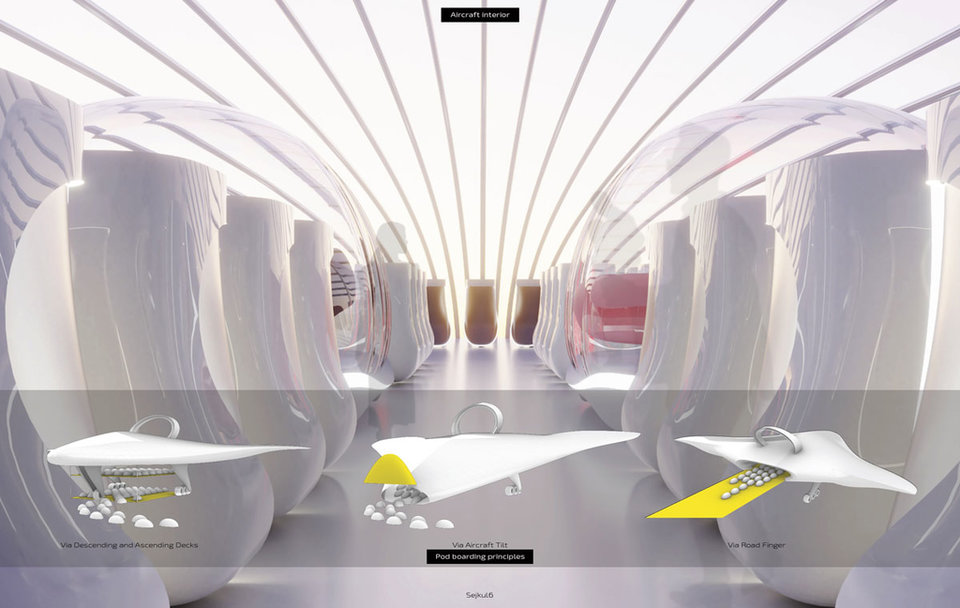

The runner-up was Dušan Sekulić, a student from Slovenia’s University of Ljubljana who gave Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport a futuristic makeover that involved autonomous traveller pods, AI-powered navigation and vertical take-off and landing. Finally, students from Beijing Jiaotong University grabbed third place with their Floating Zero City, a re-invention of Hong Kong Airport as a floating building standing on a three-dimensional platform.

As he prepares to launch a new edition after a particularly tough year for global airports, Fentress Architects principal-in-charge and Global Challenge founder Curtis Fentress talks about the winners and the themes that could dominate airport design in the future.

Floating Zero City, a reinvention of Hong Kong Airport. Credit: Fentress Architects

Adele Berti: What key characteristics do you look for in the winning design?

Curtis Fentress: Each year we're looking to see what innovative ideas people have and identify creative designers. The criteria we focus on are the overall approach to the design, and the response to site and sense of place. We also look at sustainability and resilience, which are crucial today with sea levels rising, [the need to] use renewable energies and to reduce our carbon footprint.

The fourth one is a diversity of aviation technology, as there are different types of technology like hypersonic planes, vertical take-off planes, flying cars – all of them might seem futuristic in some ways but they're coming along very quickly.

Have any of the designs ever become a reality?

Three or four years ago we had some submissions that had no apparent security blinds like the ones we have today, and they had notes on the drawings that said: “everyone will be scanned with facial recognition and biometrics”.

Today we're all talking about touchless flow through the airport, all information being stored in your phone and the airports using facial recognition. When we had a student that submitted something like that four years ago, I wondered how long it would take, and now we know that it has been accelerated by Covid-19.

Speaking of the pandemic, what role has it played in determining the winners?

Covid-19 came along after the students had been working on their designs for a while and so they turned them in just as the virus became an issue. They didn't really have time to react to a pandemic with their designs, but the jury discussed what would work well with the current situation. What we're looking for in general is flexibility because these buildings need to last 25 to 50 years or longer.

What stood out about this year’s winner?

With the title ‘Green Gateway’, it had a lot of sustainable features and ideas for airport resilience and as we looked at it, dug into it, it seemed a plausible project that it would work in the future. I was intrigued by the students’ forward-thinking, yet plausible assumption that flying cars will be made a reality by 2100 and can help to reduce the pollution caused by domestic flights.

The design also added a section showing how the airport would evolve over time and there's growth and vegetation around it, which we interpreted as a symbol of the evolution of time in an interesting and unique way. The concept also features a decentralised system of a central terminal with six multi-purpose, air-purifying towers spread throughout New Delhi. These towers significantly improve mobility across the city while also alleviating the pollution of domestic flights.

The Green Gateway — a zero-emission, sustainable hub. Credit: Fentress Architects

What new trends have you identified from judging the designs?

Technology was one of the main areas that we were seeing as we were assessing the designs. These included autonomous vehicles, pods that people might arrive at the airport in, vertical take-off and landings, hypersonic travel and even space travel and hyperloop. These are technologies that are quickly gaining momentum, and it was great to notice so many students recognising these trends and incorporating them into their designs.

An example was the second-place winner from Slovenia, who reimagined Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport as a drive-in airport where travellers navigate the terminal in autonomous pods.

Climate change is also a major consideration. A great example is this year’s third-place winner, the Floating Aero City designed by students from Beijing Jiaotong University. This concept addressed how airport design can prepare airports located in high-density seaside cities to adapt to the effects of climate change.

Floating on Hong Kong’s ocean, the airport’s three-dimensional, moveable platform reduces the impact on the natural terrain while increasing available land. However, waves in the ocean get pretty big and that makes people wonder about the design of those kinds of facilities. So, it did bring a lot of questions to the table.

What do passengers want from future airports?

We are proponents of the idea that the airport should relate to the place, it should have a relationship to the place that it exists in - you just couldn't build an airport and put it anywhere in the world. If you did, then it would be like McDonald's, which doesn’t give the flavour of the place. Denver Airport is an example, as we spent a lot of time talking about how the design should relate to the mountains.

Daylighting, clear circulation paths and exciting architecture that embraces a sense of place are also key elements to meeting passenger expectations. An example is the new South Terminal C at Orlando International Airport where we’ve designed a building that naturally guides passengers throughout the terminal using daylighting.

Technology is also paramount. Touchless technologies including biometric check-in kiosks and boarding gates will be standard features in future airports. The project team for Orlando’s South Terminal Complex has taken a swift approach to adopt these technologies by incorporating touchless features and biometrics, which will significantly reduce touchpoints for passengers.

The drive-in at Hartsfield-Jackson International. Credit: Fentress Architects

What challenges will airport designers face in the future?

For the next few decades, we're going to have public health issues, which will always be brought up in the design of the airports. Covid-19 was initially a black swan event, nobody really took it too seriously.

I travelled to Asia during SARS, and I distinctly remember flight operators taking everyone's temperature before we were allowed to disembark from the plane. And then later as I travelled to Asia, I noticed that there were monitors that were taking everybody's temperature and people that were observing the passengers and I think they were looking for symptoms.

Amid a pandemic, aviation architects are challenged to design spaces that improve wellness and give passengers space, while also remaining secure. Achieving this balance is crucial to helping the aviation industry recover. As airlines adapt their operations to the realities of changing passenger demands, architecture and design will need to keep pace to ensure airport infrastructure supports this new normal.

Main image: Fentress Architects principal-in-charge and Global Challenge founder Curtis Fentress.