Feature

Integrated airspace: a new vision for UAVs

A new white paper highlights the importance of integrated airspace for the future of commercial UAV operations. Peter Nilson outlines its core arguments.

The uncrewed aviation sector is advancing rapidly. Widespread use of uncrewed aircraft is within reach – trials have successfully demonstrated flights of uncrewed aircraft vehicles (UAVs) beyond the visual line of sight (BVLOS) of their pilot, leading to substantial innovations.

In fact, the global UAV market size was valued at $17.9bn in 2021 and is expected to expand at a CAGR of 11.17%, reaching $33.8bn by 2027.

While there have been signs that the UK Government recognises the opportunities of uncrewed aviation, including highlighting the importance of technology development and adoption in its Flightpath to the Future framework, the regulatory environment for UAVs remains complex.

While there have been signs that the UK Government recognises the opportunities of uncrewed aviation, the regulatory environment for UAVs remains complex.

The existing framework was developed with crewed aviation in mind, making it largely inadequate for uncrewed operations and for scale.

With significant investment and progress achieved, much of which was due to the Future Flight Challenge, the uncrewed sector is no longer the fledgling that it once was.

Unlocking the next steps for UAVs

Now, a new white paper is calling for the UK Government to update uncrewed aviation regulations in the country, in order to “unlock the next step on the journey of evolution”.

The paper argues that the UK risks “missing out on the drone opportunity” if it fails to remove barriers to uncrewed flight.

‘South of the Clouds: A roadmap to the next generation of uncrewed aviation’ was published by a consortium of advanced drone and technology companies that are pioneering the use of remotely piloted aircraft BVLOS, called the BVLOS Operations Forum.

“The way forward to achieving routine BVLOS operations, integrated with other air traffic, will require significant policy change from both the UK Government and the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA),” said Russell Porter, BVLOS Operations Forum chair and head of unmanned aircraft system traffic management stakeholder engagement at NATS.

We need to go further and faster if we are to make uncrewed aircraft a safe and effective option.

“While there have been positive developments, we need to go further and faster if we are to make uncrewed aircraft a safe and effective option in the aeronautical toolbox.”

The paper sets out a vision of how new types of aircraft, such as drones, can be integrated into UK airspace.

It argues that achieving routine BVLOS operations will unlock a vast array of benefits to society – including improved connectivity to remote areas; decarbonisation, both of aviation and of the wider economy; improved healthcare provisions; and increasing the safety of individuals during infrastructure inspections and other dangerous tasks.

In fact, organisations in the BVLOS Operations Forum are already using drones to deliver medical supplies to patients in remote areas; in search and rescue operations by HM Coastguard; and for conducting infrastructure inspections and monitoring in a safer and more sustainable way.

Current airspace challenges for UAVs

As the report highlights, regulations have evolved more slowly than the technologies, meaning these flights are limited to very restricted areas of airspace.

Currently, most BVLOS flights in uncontrolled airspace are required to operate segregated from other air traffic. Segregation generally requires designating a Temporary Danger Area (TDA), a Permanent Danger Area, or controlled airspace – something for which there is little precedent and guidance.

Application for a TDA requires an Airspace Change Proposal to be submitted to the CAA for review. This is a costly, and lengthy process, making it a potential inhibitor to commercial growth opportunities.

The route to the provision of services through BVLOS flight operations is currently difficult to navigate.

Once approved, TDAs can be used for a maximum duration of 90 days, after which a TDA cannot be applied for again in the same location. This ‘one-and-done’ policy currently prevents any sustained commercial operations in a single area.

“The route to the provision of services through BVLOS flight operations is currently difficult to navigate,” Porter writes in the foreword of the report.

“For most BVLOS applications, the airspace construct used to provide segregation is limited in its duration of use, time-consuming to apply for and not easily repeatable. As such, routine, scalable BVLOS operations are currently unachievable.”

Moving to an integrated airspace

Among the policy recommendations outlined in the report are updating the regulatory framework to enable routine BVLOS operations; the creation of an airspace integration roadmap; agreement on a funding mechanism for new services; and the adoption of electronic conspicuity technology – technology aids which enable UAVs to reveal and respond to their location – by 2025.

The report calls for the development of a new regulatory framework that includes clarity on future services, roles and responsibilities. It also highlights the importance of clear regulations specific to uncrewed flights that will enable routine BVLOS operations – removing the 90-day limit currently in place.

To further facilitate long-term operations, the report calls for a streamlining of the application and approval process, creating an arena for “fair and open competition” in commercial activities.

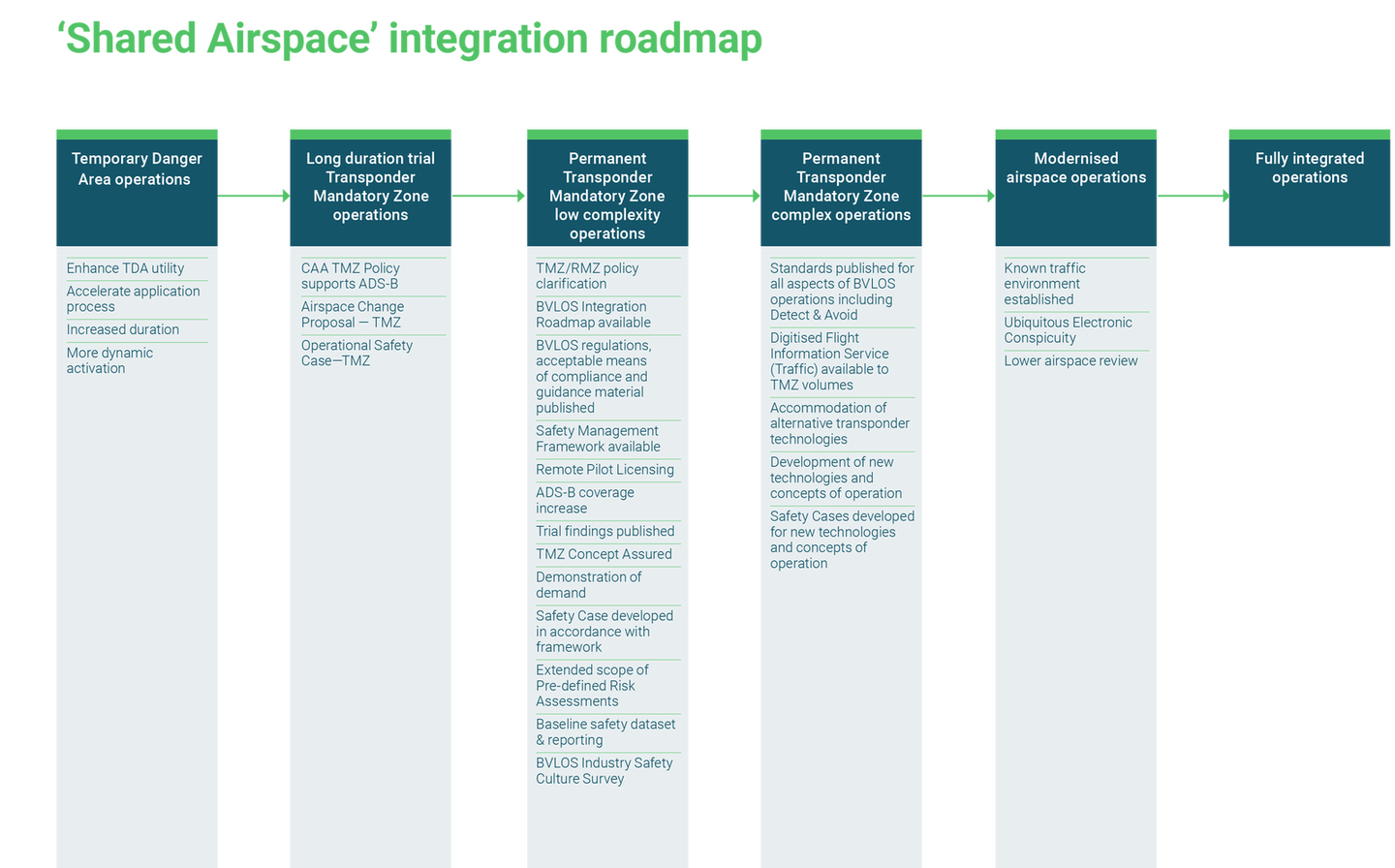

A suggested integration roadmap, developed by the BVLOS Operations Forum. Credit: BVLOS Operations Forum

The paper argues that segregated airspace that separates crewed and uncrewed aircraft is an inefficient use of airspace. Until airspace is fully integrated, “the full benefits of BVLOS will not be realised”, which the report states will result in a “two-tier” airspace economy.

As such, it recommends an airspace integration roadmap that sets out the UK Government’s desired end-state for how to achieve airspace integration, including the transitionary steps required to get there.

The development of a funding mechanism and clarity on a funding model will, the paper states, enable the investment required for “further progress and the development of infrastructure and services” that will be needed for UAV integration.

Moving to an integrated airspace

Adopting electronic conspicuity will strengthen the principle of ‘see and avoid’ by adding the ability to ‘detect and be detected’ for both crewed and uncrewed aircraft, which is key to integrating crewed and uncrewed aircraft into the same, unsegregated airspace.

Electronic conspicuity also brings well-documented safety benefits to the wider aviation community. In a fully integrated airspace, flying without electronic conspicuity would be “like driving a car at night with no headlights on”, the report states.

Electronic conspicuity can help pilots, UAV users, and air traffic management service providers to see where other aircraft are. This means all airspace users can not only ‘see and avoid’ other aircraft, but also ‘detect and be detected’ by others in a trusted manner.

Electronic Conspicuity will allow crewed and uncrewed aircraft to detect each other in integrated airspace.

Increased situational awareness is especially important when uncrewed aircraft have different flying characteristics from the crewed aircraft they operate alongside. For example, UAVs can fly lower or higher, and slower or faster than crewed aircraft.

The white paper also cites that studies have shown that human pilots find it difficult to visually detect small drones, so having such vehicles electronically detectable would greatly assist with collision avoidance.

While the paper acknowledges that there will be other requirements to ensure BVLOS operations can take place safely and efficiently, it asserts that electronic conspicuity is a “critical part” of the solution.

“With reduced emissions, reduced cost, and improved safety, uncrewed aircraft can achieve extraordinary things,” Porter said in a statement coinciding with the publication of the white paper.

“The next generation of aviation is coming, and now is the time to act to make it a reality.”